Python logging – A practical guide

Python logging isn’t easy. When I was learning python, I made many attempts to use logging in my applications. Usually I would end up frustrated and thinking that setting everything up correctly wasn’t worth the hassle. It’s only when I started building larger applications and logging became a neccessity, that I finally figured out what was going on. Learning to use python logging is rather like learning to ride a bicycle. It’s difficult to start with, but once it clicks, it’s something you’ll never forget.

This post is a step-by-step guide into the world of python logging. By the end of this guide, you should also have had that “click” moment and will be able to use python logging effectively in your application development.

This article exists in notebook format in my github repository. I highly recommend you fork or clone this respository so that you can run the code and experiment with it yourself. However, this is not a requirement to understand the content of the article.

A simple loggerPermalink

This is the most basic example of a fully functional logger. There are two main components to this logging example.

- A Logger object.

- A Handler object.

import logging

import sys

logger = logging.getLogger('package') # Create logger with name 'package'

handler = logging.StreamHandler(stream=sys.stdout)

logger.addHandler(handler)

logger.warning('This is a warning message to stdout')

This is a warning message to stdout

The logger is the primary interface for creating log messages.

We created the logger using the logging.getLogger(name) method and gave the logger the name ‘package’.

We then asked the logger to log a message by calling logger.warning. When this method is called, the logger creates a warning message (also called LogRecord). However, on it’s own, the logger can not deliver the log message. For that it needs a handler.

Handlers are specific objects whose role is to take the log message created by the logger and deliver it to wherever it needs to go. There are many types of handlers, in this example, we used a StreamHandler whose role is to pass the log message to STDOUT which is displayed by the console. For other types of handlers, check the official documentation on handlers.

Last resortPermalink

Wait a minute… I just said that a logger needed a handler to deliver messages. In the following example, I can clearly display this message in STDERR (jupyter notebook displays STDERR in red) without using a handler. So what’s going on?

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger('package') # Create logger with name 'package'

logger.warning('This is a warning message')

This is a warning message

Since python 3.2, the logging module has something called logging.lastResort. This is a StreamHandler delivering to STDERR. If no Handlers are found to deliver a message, this lastResort Handler is used. We can checkout out a few details of this lastResort Handler by printing it. As I said, this does seem to be a StreamHandler pointing to STDERR. But what does this WARNING mean? Let’s talk about log levels.

print(logging.lastResort)

<_StderrHandler stderr (WARNING)>

Log levelsPermalink

The logging module isn’t just capable of logging warning message. By default, there are 4 other types of log messages that can be produced. According to the python docs, these are the functions of each level:

- DEBUG: Detailed information, typically of interest only when diagnosing problems.

- INFO: Confirmation that things are working as expected.

- WARNING: An indication that something unexpected happened, or indicative of some problem in the near future (e.g. ‘disk space low’). The software is still working as expected.

- ERROR: Due to a more serious problem, the software has not been able to perform some function.

- CRITICAL: A serious error, indicating that the program itself may be unable to continue running.

Loggers can be configured to only accept messages of a certain severity, meaning that anything less important will be discarded. The lastResort Handler has a level of WARNING meaning that anything below (DEBUG, INFO) will be discarded. Let’s check this out.

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger('package') # Create logger with name 'package'

logger.debug('This will not be displayed.')

logger.info('Neither will this.')

logger.warning('This will be displayed!')

This will be displayed!

By default loggers also have an effective level of WARNING, meaning that even if we gave it a Handler, we would have to reset the logger level to have our logs displayed.

import logging

import sys

logger = logging.getLogger('package') # Create logger with name 'package'

print(f"This logger's level is: {logger.getEffectiveLevel()}") # 30 means WARNING

handler = logging.StreamHandler(stream=sys.stdout)

logger.addHandler(handler)

logger.debug('This will not be displayed.')

logger.setLevel(logging.DEBUG)

print(f"This logger's level is: {logger.getEffectiveLevel()}") # 10 means DEBUG

logger.debug('This will be displayed!')

This logger's level is: 30

This logger's level is: 10

This will be displayed!

basicConfig and the root loggerPermalink

So far we have been creating our own logger object called ‘package’. But the logging module contains a default logger call the “root” logger. This logger can be retrieved simply with getLogger() (without the name parameter). Let’s examine this root logger.

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger()

print(f"Root logger's handlers: {logger.handlers}")

print(f"Root logger's level: {logger.getEffectiveLevel()}")

Root logger's handlers: []

Root logger's level: 30

Nothing surpising so far. The root logger looks just like any other logger: no Handlers and a default level of WARNING. But there are a few things that differentiate the root logger from the other loggers. Look at this:

logger.warning("This will be displayed. But what's this formatting!?")

WARNING:root:This will be displayed. But what's this formatting!?

With any other logger, if no Handlers are available to deliver the message, then the lastResort Handler will be used. With the root logger, if the logging module discovers you are calling a message and there are no Handlers on the root logger, a function called logging.basicConfig() will be called. This function adds a default StreamHandler to the root logger and associates it with what is called a Formatter. We’ll talk more about formatters in a second, but let’s look into what has just happened.

print(f"Root logger's handlers: {logger.handlers}")

[handler] = logger.handlers

print(f"Handler's formatters: {handler.formatter}")

Root logger's handlers: [<StreamHandler stderr (NOTSET)>]

Handler's formatters: <logging.Formatter object at 0x7f8b0bf94310>

A handler does indeed appear to have been automatically added to the root logger.

This makes sense, the logging module is basically making it easy for anyone to write a simple, formatter log without having to understand or know about handlers or formatters. You can even call the log functions directly from the logging module itself without even retrieving a reference to the root logger!

logging.warning('A log created directly on the root logger!')

WARNING:root:A log created directly on the root logger!

Hopefully from the previous examples you have good understanding of loggers and handlers. Creating loggers with different names allows you to add different handlers to your loggers and therefore deal with logging messages differently. For instance, you can attatch a StreamHandler to one logger, and a FileHandler to another so that some messages are sent to the console and others are sent to a file!

Now let’s take a look at Formatters and how you can add formatters to handlers to modify the default message format.

FormattersPermalink

The default formatting for log messages (as seen with the StreamHandler in the first example) is to simply display the message. We have also seen how calling logging.basicConfig() adds a formatter to the root logger and which generates the following logs:

LOG_LEVEL:LOGGER_NAME:LOG_MESSAGE

Let’s extend our first example by adding our own formatter:

let’s add two handlers to our logger, one with a handler and another without.

import logging

import sys

logger = logging.getLogger('package') # Create logger with name 'package'

handler_without_formatter = logging.StreamHandler(stream=sys.stdout)

logger.addHandler(handler_without_formatter)

handler_with_formatter = logging.StreamHandler(stream=sys.stdout)

formatter = logging.Formatter('%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s')

handler_with_formatter.setFormatter(formatter)

logger.addHandler(handler_with_formatter)

logger.warning('This message will be displayed with and without formatting!')

from IPython.core.display import HTML

HTML("<script>Jupyter.notebook.kernel.restart()</script>")

This message will be displayed with and without formatting!

2020-03-29 16:30:36,910 - package - WARNING - This message will be displayed with and without formatting!

Our format displays some very useful information, it contains the time at which the log was created, the name of the logger that was called, the level (i.e severity) of the log message and the message itself. This information makes our log messages a lot more interpretable.

And that’s really all there is to know about formatting. If you want more information about which attributes can be displayed in the log message, take a look at the official documentation. In particular the list of LogRecord attributes describes how you can generate your own formatting string.

Python logging is powerful: FiltersPermalink

We’ve seen how we can create an arbitrary number of loggers, and any number of handlers to these loggers and format each message individually using formatters. That’s already a lot! What more might you want? Python provides even more flexibility with filters. Filters are objects that can be attached to loggers or handlers and determine whether a message gets processed or dropped. You can see levels as a sort of automatically applied filter. If the log is above the level of the logger (or handler) it gets processed, otherwise it’s dropped.

Since python 3.2, the simplest way to create a filter is with a function. It must take as input a log message, and output zero, if the LogRecord is to be dropped and non-zero otherwise. Let’s go back to our simple example. I have added type hinting to the function to emphasise the input and output of a valid filter function.

import logging

from logging import LogRecord

import sys

def gandalf_filter(log_record: LogRecord) -> int:

"""A simple filter.

This filter drops logs that contain

the string 'you shall not pass' in their message.

"""

if 'you shall not pass' in log_record.msg:

return 0

else:

return 1

logger = logging.getLogger('package') # Create logger with name 'package'

handler = logging.StreamHandler(stream=sys.stdout)

handler.addFilter(gandalf_filter)

logger.addHandler(handler)

logger.warning('This message will pass!')

logger.warning('This message will not pass: you shall not pass')

This message will pass!

You can pretty much do whatever you want with the LogRecord, you can even modify it in place to change the message.

import logging

from logging import LogRecord

import sys

def gandalf_the_white_filter(log_record: LogRecord):

"""A simple filter.

Adds ' the white' to a log message if it ends with gandalf.

"""

if log_record.msg.endswith('gandalf'):

log_record.msg = log_record.msg + ' the white'

return 1

logger = logging.getLogger('package') # Create logger with name 'package'

handler = logging.StreamHandler(stream=sys.stdout)

handler.addFilter(gandalf_the_white_filter)

logger.addHandler(handler)

logger.warning('I am gandalf')

logger.warning('You shall not pass!')

I am gandalf the white

You shall not pass!

You are now familiar with the 4 main components of python logging:

- Loggers

- Handlers

- Formatters

- Filters

You should be able to set up some pretty fancy logging with all that knowledge. There’s one last thing I would like to tell you about: logger hierarchy.

Logger hierarchy in python loggingPermalink

There’s something I have been hiding from you. Python loggers are not independent. They are organised in a hierarchy with the root logger at the top. This raises a couple of questions…

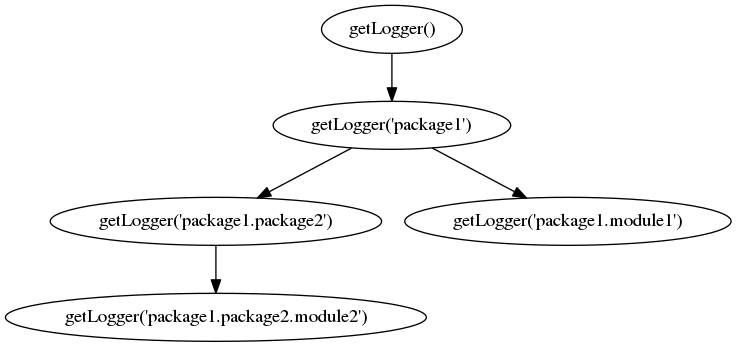

How do you create a hierarchy?Permalink

Firstly, all loggers are children of the root logger.

Secondly, hierarchy is specified by a dot-separated naming convention.

For instance, a logger named ‘package1’ is a child of the root logger and a logger named ‘package1.module1’ is a child of the ‘package1’ logger and the root logger.

What does this hierarchy do?Permalink

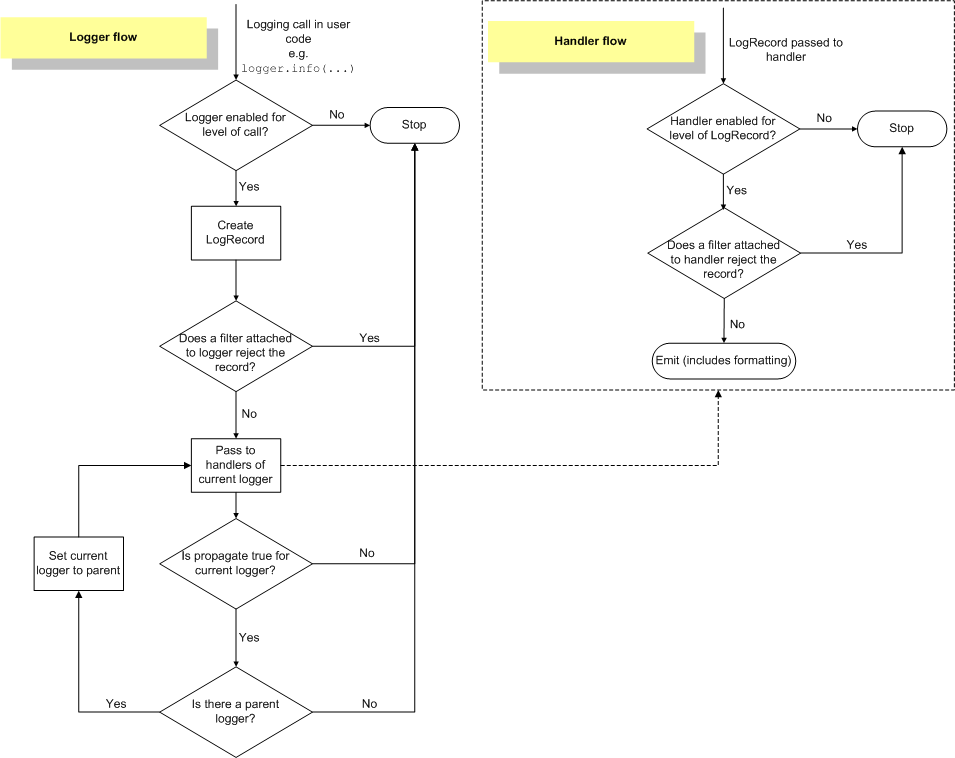

This hierarchy has several effects. When a child logger creates a log message (and that message passes the filters of that logger) all handlers of parent loggers of that child will receive this message. Let’s take a look at an example:

import logging

import sys

handler = logging.StreamHandler(stream=sys.stdout)

logger = logging.getLogger('package') # Create logger with name 'package'

logger.addHandler(handler)

child_logger = logging.getLogger('package.module')

child_logger.addHandler(handler)

child_logger.warning('This will be printed by the parent and child handlers.')

from IPython.core.display import HTML

HTML("<script>Jupyter.notebook.kernel.restart()</script>")

This will be printed by the parent and child handlers.

This will be printed by the parent and child handlers.

It is possible to disable the propagation of LogRecords to the parent’s handlers by setting “logger.propagate = False” on the logger:

import logging

import sys

handler = logging.StreamHandler(stream=sys.stdout)

logger = logging.getLogger('package') # Create logger with name 'package'

logger.addHandler(handler)

child_logger = logging.getLogger('package.module')

child_logger.addHandler(handler)

child_logger.propagate = False # Prevent propagation of the LogRecord to parent handlers.

child_logger.warning('This will be only be printed by the child logger.')

from IPython.core.display import HTML

HTML("<script>Jupyter.notebook.kernel.restart()</script>")

This will be only be printed by the child logger.

The python documentation contains an excellent diagram explaining how a LogRecord gets created by a logger and then passed to all parents. I will display that diagram here, but the original can be found in the official python logging documentation.

The second major effect of this hierarchy is that the level of a logger can be determined by its parents. For instance, if a child logger does not have a level set (logging.NOTSET), then the logging module will move up the chain of child parents until it finds a level that is set and will use that level. This level is called the “effective level” for that logger. Let’s take a look:

import logging

import sys

logger = logging.getLogger('package') # Create logger with name 'package'

root_logger = logging.getLogger()

print(f"The logger's level is: {logger.level}") # 0 == logging.NOTSET

print(f"The root logger's level is: {root_logger.level}") # 30 == logging.WARNING

print(f"This logger's effective level is: {logger.getEffectiveLevel()}") # 30 == logging.WARNING

from IPython.core.display import HTML

HTML("<script>Jupyter.notebook.kernel.restart()</script>")

The logger's level is: 0

The root logger's level is: 30

This logger's effective level is: 30

As you can see, the level of the logger is NOTSET, hence the logging module will search the parent loggers until it finds one with a level different from NOTSET. The only parent of ‘package’ is the root logger and we know that this logger has a log level of WARNING by default. Therefore, the logger’s effective level is 30. It’s the effective level (not the logger.level attribute) that determines whether a log message gets passed to the handlers.

The LogRecord being passed to handlers and the effective level of loggers are the main effects of the logging hierarchy. The logging hierarchy is useful for not having to add handlers to every single logger you create. You might be wondering what’s the point in creating child loggers if the messages get passed to the parent handlers anyway. That’s a great question, and to understand, you need to know how naming is generally used in logging for large python applications.

In my graph of “logging hierarchy” you might have noticed that I named the loggers “package” and “module”. This is because, when developping packages, it’s best practice to create a logger for every module and for each logger to be named according to its location in the package. This becomes very useful when you want to find out about the provenance of logging messages because formatters can include the name of the logger in the log message itself. Another advantage of naming loggers with the names of your modules and packages it prevents collisions with other loggers from other packages.

hint: You can use the variable __loader__.name to automatically retrieve the full path to the module in a package. Contrary to __name__ which gets given the value ‘__main__’ when the module is used as an entrypoint, __loader__.name will contain the full module name even if it’s the entry point of the application.

Application logging vs library loggingPermalink

You now know almost everything you need to build the most amazing logging for your applications.

However, so far I have mainly described the python logging module and its functionality. I have not talked about which logging functionality should be used when.

When deciding how to write your logs, you should ask yourself the question:

- Am I writing a library?

- Am I writing an application?

A library is intended to be used by other software developers as a foundation. An application is intended to be used by yourself or your clients directly.

Logging for a libraryPermalink

When developing a library, it is recommended not to add handlers to your loggers. Instead, just let the LogRecords flow to the root logger and if the user of your library wants to do something with your logs, they can create the handler and formatters they want. Even better is to add a logging.NullHandler() to the base of your logging hierarchy (i.e getLogger(‘package’)). That way, if the user of your library does not configure logging for their application, your messages won’t be displayed by the lastResort handler. This is described in more detail in the official documentation on configuring logging for a library.

Logging for an applicationPermalink

- Your application is a part in a larger multi process application:

The best practice for logging within a large application is to only send messages to STDOUT (i.e only use StreamHandlers(stream=sys.stdout)). By doing that, you are essentially delegating the role of storing logs to your application’s environment. Imagine if your application is one process in a larger multiprocess application with each sending its logs somewhere different. It would be a nightmare for the application environment to compile all the logs and analyse them together. If all processes send their logs to STDOUT, the environment knows where everything is and can decide what to do with the STDOUT stream. - Your application is standalone

If your application is standalone, and not being managed by some external process, then it’s OK to be handling the output of your log yourself. In that case, you can configure logging for your application with a configuration file or directly in code as we have been doing so far.

ConclusionPermalink

If you’ve reached this point, well done and thank you! This guide has taken you through all the major components of python logging. We’ve even touched upon best practices when logging in large applications or libraries. The python logging module is extremely powerful. Good logging practices can help immensely with debugging and healthchecking your application, so go ahead and start experimenting.

If you’ve found the content of this article useful, I highly recommend checking out some of my other articles. This post is part of a series on python development fundamentals. If you’re wondering how to structure your python application, then take a look at my article on the optimal python project structure.